I am excited to host a guest blog by historian Sean Cunningham today. The following post is an excerpt from his latest book, Prince Arthur: The Tudor King Who Never Was.

I am excited to host a guest blog by historian Sean Cunningham today. The following post is an excerpt from his latest book, Prince Arthur: The Tudor King Who Never Was.

Prince Arthur, the Mortimers and the search for Tudor legitimacy

Even as an infant, Prince Arthur’s complex ancestry was essential to the Tudor regime’s claims to legitimacy. Until the prince was born, King Henry VII’s position was secured only by right of conquest and the military muscle of the nobles who had put him on the throne. His rule was not sustainable while it was largely reliant on their continuing loyalty. At that early stage of the reign, their combined power could still overawe that of the royal family and members of the king’s household. Richard III had found that allies could turn or remain indifferent at the crucial moment even after firm promises of support. Henry VII therefore knew that had to broaden his appeal, and Arthur had a key role in that process.

When Queen Elizabeth presented Henry with a healthy baby boy on 20 September 1486, the king seems already to have formed a plan built upon much older dynastic and geographical links that his new son would absorb and carry into the future. Ceremonies surrounding Arthur’s naming, birth and christening were stage-managed at Winchester to emphasise that Henry VII’s family were directly connected to King Arthur and the ancient rulers of Britain. After a period in a closed nursery at Farnham Palace in Surrey, the prince’s education was to continue in the Welsh Marches; a region with strong links to Arthurian legend that re-emphasised Prince Arthur’s blood ties to undisputed regional lords with strong royal ancestry.

Ludlow Castle

In sending Arthur to Ludlow Castle in Shropshire, King Henry proclaimed his intention to duplicate the education and training put in place for the first Yorkist Prince of Wales, the future Edward V, in the early 1470s. Twenty years later, by spring 1493, at the age of six, Arthur was required to move far away from his family and live as a semi-independent lord on the March. Of course, he would have counsellors, tutors, servants, friends and confidants to aid his growth into his royal role. But this arrangement was intended to deliver more than an elite education. The king wanted to supply his son with practical training based on direct responsibility. Initially, it was true that Arthur had limited capacity to engage with his legal obligations, estate management or assessment of the personal qualities of his servants. That would all come with experience; and all-the-more quickly if Arthur learned from mistakes as he made them. The king knew that, too. Henry wanted his son to build bonds of trust with a small group of loyalists in the same way that he had managed towards the end of his exile in Brittany and France in 1483. That inner-circle could then carry Arthur to adult rule or at least support him through a minority or regency until he could reign alone.

There was also a greater sense of urgency in Henry VII’s delegation of power to his son than Edward IV had demonstrated with Prince Edward. Arthur’s development was intended to build his leadership skills as quickly as possible. A confident and capable prince would inspire lasting support. The king perhaps had one eye on his personal vulnerability – already demonstrated by at least five major conspiracies and risings before 1491. In the event of King Henry having to face another pressing crisis, concerted challenge or even deposition (and Perkin Warbeck threatened all three from 1493), he needed an heir who was capable of leading an alternative government backed by experienced men who were also loyal. Henry could shape his planning in this area by drawing on the example of the outmanoeuvring and scattering of Prince Edward’s Ludlow household by Richard, duke of Gloucester in April-May 1483.

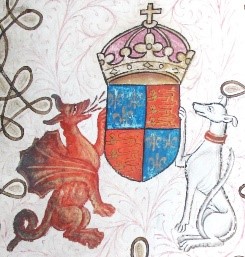

Cadwaladr’s red dragon as a supporter of Henry VII’s arms, along with the greyhound of the king’s earldom of Richmond.

King Henry was aware that the spectre of civil war hovered in the background of each day of his reign. While he embodied the Tudor regime’s authority, it would remain vulnerable to any direct attack. Arthur’s separation from the rest of his family therefore gave the regime two centres of power; which reduced the impact of the Tudor crown’s initial deficiency in firm allies. As the prince started to learn how to make decisions, the crown began a deliberate campaign to attach Arthur to Anglo-Welsh society. That process involved a clever reinterpretation of regional history that put the new Tudor prince at the centre of an older story.

Arthur’s homeland became the region between, Shrewsbury, Wigmore, Bewdley, Ludlow, Weobley, Worcester, Leominster and Hereford. This was the centre of power for the Prince of Wales, and the area over which his Council of the Marches of Wales dominated as representative of the more distant Westminster government. It was also the historic heartland of the lordship of the earldom of March and the powerful Mortimer family.

The last earl of March had been Edward V before April 1483. Once he was believed to be dead and Richard III perished on the battlefield, Arthur’s mother, Princess Elizabeth, became the last direct heir of the Yorkist kings. She was also the most prominent living descendant of the Mortimers as earls of March. Transplanting Arthur to Ludlow emphasised his maternal lineage to the Mortimer family. The move replaced the Yorkist prince with a Tudor one in the hope that regional loyalties would soon follow.

The earldom had for many years underpinned the House of York’s power and had formed part of its claim to the throne. Elizabeth’s grandfather, Richard 3rd duke of York had been a product of the marriage of Anne Mortimer and Richard, earl of Cambridge, one of Edward III’s grandsons. Anne was the sister of the last Mortimer earl of March – Edmund Mortimer who had died in 1425. Richard, duke of York had inherited the Mortimer estates and the dormant Mortimer claim to the crown through descent from Edward III. It was Edward IV that brought this fusion of rights and entitlements together when he became king in March 1461.

The white hart badge used by Edward IV as heir of Roger Mortimer, 4th earl of March, who was himself named heir of Richard II. The white hart was prominent on banners at Arthur’s funeral in April 1502. From a misericord in St Laurence church, Ludlow

Edward consciously proclaimed this aspect of his genealogy when he quickly annulled the attainder of Richard earl of Cambridge. Anne Mortimer herself was also a direct descendant of Edward III’s second surviving son, Lionel, duke of Clarence. Lionel’s only daughter Philippa had married Edmund Mortimer, 3rd earl of March and was Anne’s grandmother. It was this dual ancestry to Edward III that led to Roger Mortimer being proclaimed in parliament as Richard II’s heir in 1385. His death in Ireland in 1398 allowed the claim of Henry of Bolingbroke, duke of Lancaster, to build momentum. Henry’s seizure of the crown in 1399 led to the opposition of the Mortimer family group to the Lancastrian kings. It was also a longer-term factor in maintaining belief in the royal rights of Richard, 3rd duke of York during the 1450s. When Edward IV decided to locate the household of his eldest son in the Welsh Marches he was reconnecting the dynastic roots of the Yorkist crown with its regional and royal origins in the legitimate but side-lined rights of the Mortimer family.

The Mortimer connections of his heir allowed Henry VII to attach his own British ancestry in this area. Henry made much of his descent from Brutus and his links to Cadwaladr ap Cadwallon, the last king of all Britain. This approach extended the Arthurian imagery displayed at Arthur’s christening in Winchester. Henry VII’s use of the legends of early Britain was also essential for a general acceptance of Prince Arthur’s inheritance of Mortimer power. The Mortimer family had shown considerable interest in the Arthurian stories as part of their genealogy. The legendary figures Cadwaladr, Brutus and Arthur were viewed as ancestors and not mythological predecessors. When the Mortimers married into the family line of Llewelyn ap Iorwerth in 1228 they absorbed the descent of the princes of Wales growing from Cadwaladr. Arthurian tradition continued to be heavily promoted by the Mortimers as they developed their relationship with the English crown during Edward I’s war with Prince Llewelyn ap Gruffydd.

Later Plantagenet kings allowed the family to build up vice-regal authority along the border from their castles and estates at Wigmore, Ludlow, Cleobury and Chirk. The earls of March claimed a direct connection to the key events of King Arthur’s life through physical features and remains found on Mortimer estates. The reinvention of the Arthurian myth reached the centre of crown power during the late fourteenth century; to the point where Roger Mortimer, 4th earl of March was, by 1398, a short step away from becoming king.

When the Mortimers and their heirs reconnected with great leaders of historic Britain they emphasised that their personal power was deep and strong, and was offered to the English crown in alliance and not through subjugation. For this relationship with the March to become a valuable platform for Arthur’s personal power, he had to present himself as the direct descendant of those dominant border figures who stood as partners and representatives of the English king without being wholly subject to his lordship.

When Edward IV had been earl of March, his drive to depose Henry VI in 1460-61 was partly based on his command of the men of the Welsh borderlands. The early battles of the Wars of the Roses, at Blore Heath and Ludford Bridge in the autumn of 1459, were fought as attempts to damage the ability of the Yorkist forces to draw on the resources of the March. A century of opposition to the legitimacy of the Lancastrian crown by the Mortimer/York group therefore presented Henry VII with some major problems once he intended that his son should take on the mantle of earl of March at the same time as he, the king, was identified as the last heir of Lancaster. The crucial factor was the emphasis on Arthur’s personal right as the inheritor of his mother’s Mortimer blood. This is seen most obviously in the heraldry of Mortimer, York and Cadwaladr used in imagery associated with Arthur, both in the Marches and in state occasions like his wedding pageants and funeral procession.

Prince Arthur in Victorian stained glass in St Laurence Church, Ludlow

The Yorkists exiled by Richard III’s coup agreed to back Henry Tudor’s claim on the basis of his promise to marry Princess Elizabeth. Marriage and the prospect of an heir allowed Henry to map and exploit Elizabeth’s recent genealogical connections to kings with undisputed royal rights and glories; both real and legendary. Henry’s personal descent in the male line soon entered the ranks of north Welsh landholders, so it easy to see why his courting of the Yorkist lords and gentry was so crucial to his slender grip on national power after Bosworth. The role planned for Arthur also deepened this association.

In November 1493 Arthur was formally granted the lands and rights of the earldom of March. At the same time, he merged the real and the mythical associations of the earldom with his personal leadership. Securing the resources of the earl of March gave Arthur’s power a regional focus that was arguably more important to his father’s regime than his creation as Prince of Wales in November 1489. The ready-formed network of the marcher region provided Arthur with the land-based ties of service and lordship that Henry Tudor had never enjoyed before he was king. They would be the key factors in ensuring that Arthur would have a secure basis to his rule when he did inherit the crown. Although this was a situation that never came to pass, Henry had put in place all the mechanisms that could ensure a smooth transfer of power to Prince Arthur. His death in April 1502 shattered the king’s plans for the future of the crown and required a new strategy to be built around the less-promising figure of the eleven-year-old Prince Henry.

In November 1493 Arthur was formally granted the lands and rights of the earldom of March. At the same time, he merged the real and the mythical associations of the earldom with his personal leadership. Securing the resources of the earl of March gave Arthur’s power a regional focus that was arguably more important to his father’s regime than his creation as Prince of Wales in November 1489. The ready-formed network of the marcher region provided Arthur with the land-based ties of service and lordship that Henry Tudor had never enjoyed before he was king. They would be the key factors in ensuring that Arthur would have a secure basis to his rule when he did inherit the crown. Although this was a situation that never came to pass, Henry had put in place all the mechanisms that could ensure a smooth transfer of power to Prince Arthur. His death in April 1502 shattered the king’s plans for the future of the crown and required a new strategy to be built around the less-promising figure of the eleven-year-old Prince Henry.

——-End of Excerpt——-

Prince Arthur: The Tudor King Who Never Was is available now in the UK and will be available in the US later this year. It is published by Amberley Publishing.