Today I am pleased to announce a guest post from Annie Whitehead, author of Women of Power in Anglo-Saxon England. This book offers a fascinating glimpse into the women behind the scenes in Anglo-Saxon England.

I’m so pleased to be here today as Kristie’s guest. My new book details the lives of over 100 women, some of whom had their careers well documented and some of whom were barely mentioned, leaving me quite a bit of detective work to do. Often I’ve been asked why I’m so drawn to these women and I think it’s because they defy assumptions about their lives. So, in light-hearted vein, I’d like to present:

An A-Z (almost) of Anglo-Saxon Women

A is for Æthelburh, a little-known queen regent who got cross and burned a town to the ground. She also had the servants trash the royal hall to prove a point to her husband about the dangers of valuing material things.

B is for Burhs. These are the defensive towns which Æthelflæd, Lady of the Mercians, built. Æthelflæd ruled a kingdom and was instrumental in forcing out the invading Vikings.

Cynethryth coin replica,

Author’s collection

C is for Cynethryth. She is the only queen (that we know of) who had coins minted in her own name and with her own image.

D is for Domneva. She tricked a king into giving her land to build an abbey.

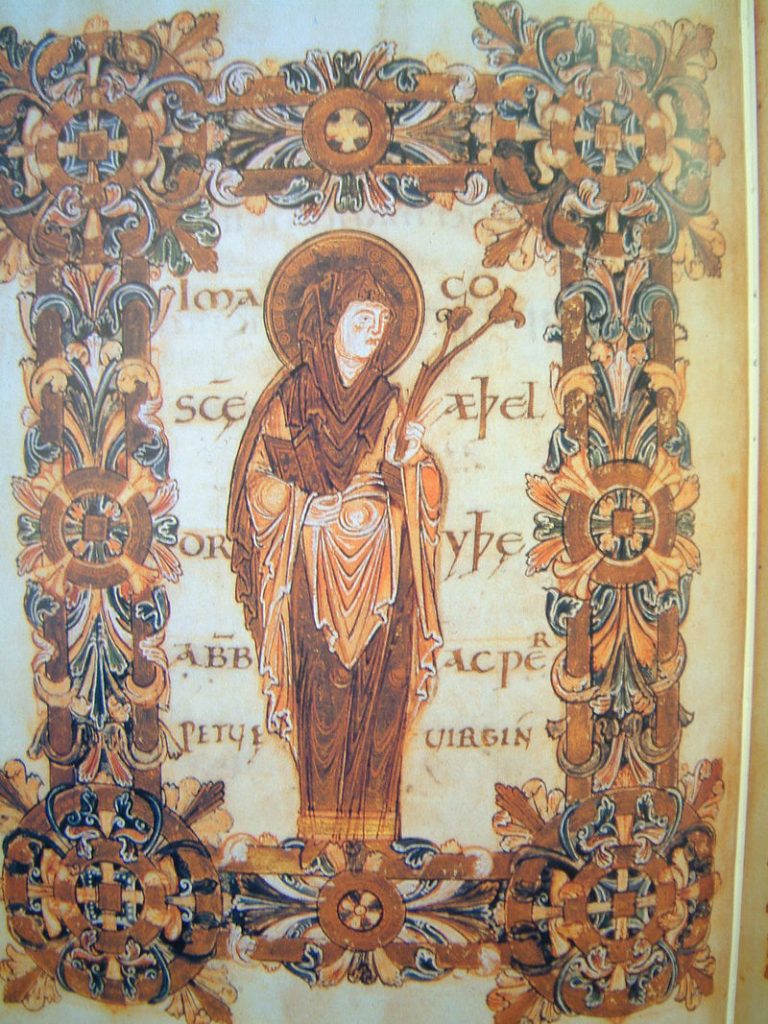

Edith of Wilton

E is for St Edith of Wilton. She was a nun and a princess, and a bishop told her off for her snappy dress sense. She ignored him.

F is for Fladbury, the site of an abbey and possibly named after Ælfflæd, daughter of King Oswiu of Northumbria. Her testimony was used to secure the throne for a king after a succession dispute.

G is for Godiva. She most likely didn’t ride round Coventry naked, but she belonged to a powerful family and she lived to a ripe old age.

H is for Hild. She founded Whitby Abbey where her nuns produced books, and she educated no fewer than five future bishops.

I is for Iurminburg, wife of a Northumbrian king. She was accused of stealing a reliquary from St Wilfrid and dancing around with it in triumph while Wilfrid languished in prison.

J is for Judith of Flanders. She married a king of Wessex, and when he died she married his son. When he died, her father put her under the watch of a bishop, but she eloped and married again!

‘Balduin Judita’ is image of Judith of Flanders and her third husband, Baldwin of Flanders

K is for Kenelm. His sister, a princess and abbess, was accused of arranging his murder, and when she cast a spell to avoid discovery, her eyeballs fell out. Apparently.

L is for Lyminge, an abbey founded by Æthelburh, a Kentish princess who married a Northumbrian king. Endearingly, we know that she had a nickname, Tate, which comes to us from the pages of Bede’s History of the English People.

M is for St Margaret. She married the Scottish king, Malcolm Canmore, but she was descended from the Anglo-Saxon royal family (her father was briefly declared heir to the throne in 1066) and her daughter married Henry I of England, thus bringing the Anglo-Saxon and Norman blood lines together.

St Margaret’s Shrine

Author’s Collection

N is for Northampton. A woman known as Ælfgifu of Northampton married King Cnut, who sent her to rule Norway on behalf of their son. She then fought successfully for her other son to become crowned king of England.

O is for Osthryth. A rather sad tale here, for she was married off to her father’s enemy and was subsequently murdered by the nobles in her new home.

P is for Pega, the sister of the hermit St Guthlac. One legend says the devil took on her appearance to tempt Guthlac to eat before sunset, contrary to his vows, but Guthlac actually entrusted no one but her with the task of tending to his body when he died.

Q is for Queen, which was allegedly not a name given to the wives of Wessex kings, on account of one of them accidentally poisoning her husband whilst attempting to murder his counsellor.

R is for Rhianfellt, a princess of the British kingdom of Rheged. Her children by a future king of Northumbria married into the family of their father’s enemies. The son became king after his father, while the daughter was accused of murdering her husband.

S is for Seaxburh. A very special woman indeed, who is the only one ever to be included on a Regnal List. A rarity, but a queen nevertheless.

Æthelthryth

T is for Tawdry. The word, meaning shoddy or of bad quality, came from St Æthelthryth, or Audrey. On her feast day, the market would become swamped with inferior souvenirs.

U is for Uhtred of Bamburgh (not the Bernard Cornwell character). His wife was a daughter of Æthelred the Unready, and Uhtred was killed by her sister’s husband. I wonder how this affected the relationship between the sisters, although sadly we’ll never know.

V is for Vikings. There are many stories but one dramatic (and anachronistic) tale records how one brave abbess deliberately cut off her nose and exhorted her nuns to do the same, so that they would not be ‘tempting’ for the marauders.

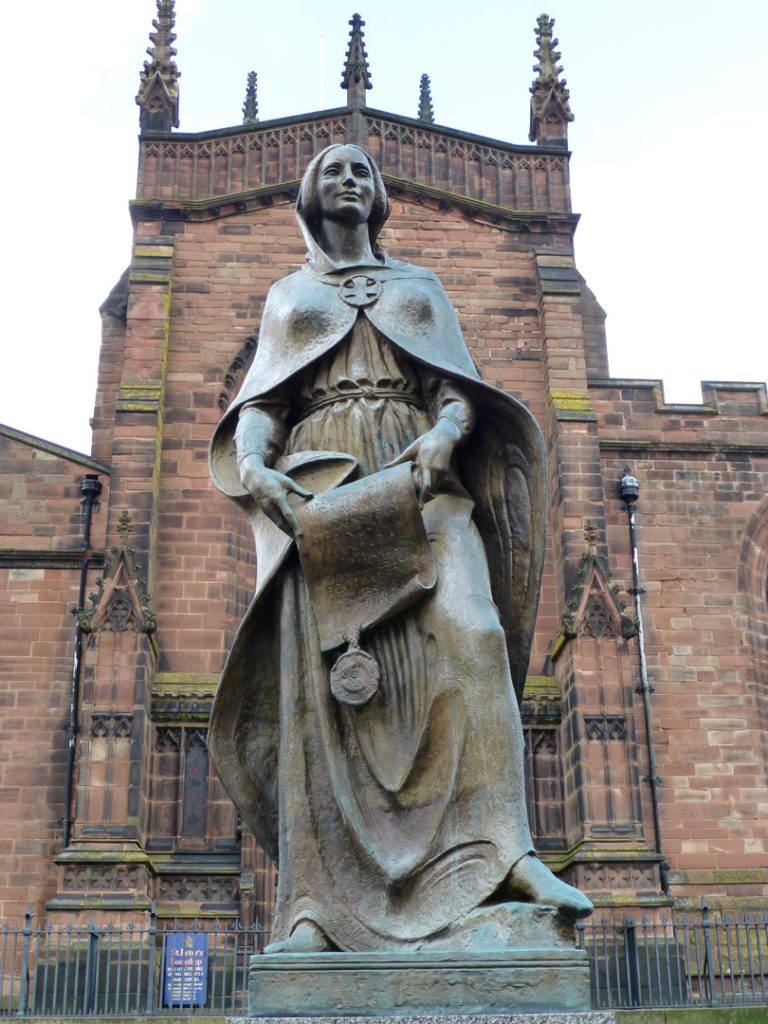

Wulfrun Statue

Attribution Link:

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Lady_Wulfrun_statue.jpg

W is for Wulfrun. A high-status woman who was taken hostage by the Danes, and after whom the town of Wolverhampton is named.

Y is for Ymme, the wife of a king of Kent. One of a number of women who are mentioned only once by name. Tracking these women down is not always easy.

There is no X and there is no Z. They simply didn’t form part of the Old English alphabet. I hope no one minds though, because I think there are plenty of interesting Anglo-Saxon women in the rest of the alphabet!

About the Author

Annie’s book, Women of Power in Anglo-Saxon England, was published by Pen & Sword Books in June 2020. It can be purchased from P&S (https://www.pen-and-sword.co.uk/Women-of-Power-in-Anglo-Saxon-England-Hardback/p/17769) and online (http://mybook.to/WomeninPower)

Annie is an author and historian and an elected member of the Royal Historical Society and has won awards and prizes for her fiction and nonfiction.

Published works include Mercia: The Rise and Fall of a Kingdom (Amberley Books) and novels and stories set in Anglo-Saxon England, including To Be A Queen, the story of Æthelflæd, Lady of the Mercians, longlisted for HNS Book of the Year 2016. She was the inaugural winner of the Dorothy Dunnett/HWA Short Story Competition in 2017.

You can connect with Annie through her Website (https://anniewhiteheadauthor.co.uk/) on Facebook (https://www.facebook.com/anniewhiteheadauthor/), Twitter (https://twitter.com/AnnieWHistory) and on her Blog (https://anniewhitehead2.blogspot.com/) and Amazon Author Page (http://viewauthor.at/Annie-Whitehead)